Part II

Published by Soka Spirit Editor

Posted on May 16, 2015

Intro: In his preface to a book called the Bennaku Kanjin-sho, sixty-fifth High Priest Nichijun Shonin writes: “Those who practice this Buddhism must pay heed to the path of the master and disciple, trace the orthodoxy of the master’s lineage to verify that the flow of the Law he transmits is correct, and [only] then partake of its pure water. The historical rationale of this is that in the school of Nichiren Daishonin, it is as clear as the sun is bright that the succession of theTransmission of the Law which began when the Sacred Founder (Nichiren Daishonin) transferred the Heritage of the Law to Second High Priest Nikko Shonin and willed that he be the Great Master [of Propagation], and continued when Third High Priest Nichimoku Shonin in turn succeeded Nikko Shonin has continued down [through the ages] to this day. Thus, when one makes it a matter of principle to adhere to this relationship between the successive masters and disciples, one can intrinsically partake of the orthodox practice and faith.” (Reverend Jun’ei Anzawa and Reverend Hakudo Mori, 1995 Nichiren Shoshu Monthly)

In Part I, it was explained that the transmission of the heritage of the Law from the 57th to the 58th high priest was derailed by factions within the priesthood who wanted to capture the position for their ringleader Ho’un Abe—father of 67th High Priest Nikken. Unable to return to the head temple to transfer the heritage directly, Nissho instead transferred the heritage to two lay believers. Eventually, his choice for a successor, Nitchu, did assume the position, but schemes against him only intensified and the heritage again was lost.

A No-confidence Vote by Priest Assembly

Signals the End of Nitchu’s Term

An assembly meeting of Nichiren Shoshu priests began at the head temple Taiseki-ji on November 18, 1925. The assembly first dealt with measures Nichiren Shoshu would be taking against the Minobu Sect. During a November 28 session, however, the topic turned into a no-confidence vote against Nitchu and called on him to resign.

The assembly had turned suddenly from the Minobu matter to their distrust of their own high priest, resolving to oust him. Behind this resolution was a secret agreement among assembly members. It was nothing less than a coup.

The following is a rather lengthy document of charges and allegiance by priests of the assembly that was deliberated on behind the scenes:

“The current chief administrator, Nitchu Shonin, violates the Rules of this school with his biased view and judgment. We assert that he lacks the ability to govern this school. We demand that the high priest quickly retire to bring a fresh breeze of renovation to this school. For this reason, we have come to the following agreement, with our pledge in front of the three treasures of Buddhism that all we write here is true. The following are various aspects of Chief Administrator Nitchu’s unjust behavior.

- He has no intention to select the next study chief.

- He has no policy to enhance study and promote propagation.

- When he took over financial contribution matters in August 1924, he mismanaged them.

- He orchestrated the demotion of Ho’un Abe in the hierarchy of priesthood.

- By not abiding by the official rules, he made it impossible for chief priests and teachers to execute their responsibilities.

- He disregarded the teachers of this school.

- He allowed his wife and children to reside at Renzo-bo, the official residence of the study chief.

- The revision of the Rules and Bylaws of this school has been a vital matter for more than ten years. All have wanted to see this revision carried out, but his weak leadership prevented any proposal from being put forth. This indicates that he is unqualified to lead the entire school.

Proposed are the following practical actions.

- We recommend Jirin Hori to become the next chief administrator.

- We propose executing a major revision of the Rules and Bylaws of this school and plan a major study renovation.

- Clarification of the head temple’s assets. [There was confusion over just what were the assets of the head temple and accounting for them.]

In adopting these points, we understand there will be repercussions if they are violated. We sign our names here to express our agreement with all the above points.”

November 18 in the 14th year of Taisho [1925]

Assembly members: Koken Shimoyama, Jiyu Hayase, Gido Miyamoto, Jimon Ogasawara, Gyodo Matsunaga, Shuin Mizutani, Korin Shimoyama, Shohei Fukushige, Ryodo Watanabe, Shudo Mizutani, Jizen Inoue

Council members: Shudo Mizutani, Koben Kogyoku, Kohaku Ohta, Jiyu Hayase, Gyodo Matsunaga, Jimyo Tomita, Teiyu Matsumoto, Shinkei Nishikawa, Koga Arimoto, Yodo Sakamoto, Kosei Nakajima, Bungaku Soma, Shundo Sato, Jisen Shiraishi, Shodo Sakio

The initial part of this document harshly criticizes the high priest, asserting: “The current chief administrator, Nitchu Shonin, violates the Rules of this school with his biased view and judgment.” The document is noteworthy for expressing the intention to impeach the high priest and make him retire because, as stated, “we have come to the following agreement, with our pledge in front of the three treasures of Buddhism that all we write here is true.”

Current view on the infallibility of the high priest: “It is hardly possible for the High Priest to commit an offense of going against the Daishonin’s teachings…. No matter how many people decide and agree on an interpretation of the teachings, if the High Priest judges it wrong in light of the Heritage of the Law, we must discard it.” (October 2008 Nichiren Shoshu Monthly p. 18.)

Eight examples of Nitchu’s supposedly erroneous behavior are cited but the fourth point is especially striking: “He orchestrated the demotion of Ho’un Abe in the hierarchy of priesthood.”

Four months before the assembly convened Ho’un Abe (the future Nichikai) had been reprimanded by Nitchu. Abe was deprived of the position of general administrator and was also demoted from the position of noke priest (an elite rank from which the next high priest is selected).

Abe, in a desperate attempt to enhance his reputation, had contributed an article to the school’s publication Dai-Nichiren titled “Admonishing Shimizu Ryozan.” This article attacked remarks made in an interview by Mr. Ryozan, a scholar of Nichiren schools in Japan. When High Priest Nitchu saw the article, he was astounded at Abe’s immaturity and lack of consideration, to the point where the high priest directly reprimanded him, stating that by embarrassing the school, Abe was not suitable to be general administrator or to retain noke status in the hierarchy of priesthood. Although the Abe apologized, he was still compelled to resign from his position.

Because of this demotion, Nichikai’s path to becoming high priest was blocked. This act against Nichikai triggered the coup against Nitchu.

The document of allegiance described a planned coup against Nitchu. According to this plan, Nitchu’s successor would be Jirin Hori (who later became Nichiko, the 59th high priest).

It was believed that the trusted Nichiko Hori would have served as a steppingstone toward eventual transference of the heritage to Nichikai. If Nichikai, the chief promoter of the coup, had become high priest immediately after Nitchu’s ouster, there would have been strong opposition from Nitchu’s camp.

Head of Laity Infuriated by Demand for Nitchu’s Resignation

The coup was put into action with this November 20, 1925, resolution: “The assembly does not trust Chief Administrator and High Priest Nitchu Tsuchiya.”

They put forth a vote of no confidence in Nitchu, together with a resolution urging him to resign:

“Chief Administrator and High Priest Nitchu Tsuchiya, since his inauguration has failed in his governance of this school. Taking advantage of his position, he pursued his own gain. Abusing the authority of his position, he trampled upon the rights of the priesthood. In light of this, we can no longer entrust him with the role of governing the entire school. Therefore, we recommend his swift resignation.”

November 20 [1925]

Pressure on Nitchu consisted of more than just the assembly resolution. The resolution was made on November 20, but an incident on November 18 had already greatly disturbed Nitchu. While he was carrying out midnight gongyo in the reception hall at the head temple, someone threatened him, fired a gun outside the hall and stones were thrown at the reception hall during the ceremony.

In a February 24, 1926 investigation by local police, it was revealed that two individuals-Jinin Kato of the Nichiren Shoshu Administrative Office and Shohei Kawata, chief priest of Renjo-ji had confessed to firing a gun and throwing stones at the reception hall in an effort to intimidate High Priest Nitchu during midnight gongyo on November 18 the previous year.

These actions to disturb Nitchu during midnight gongyo were carried out by two priests, but it is apparent they were executing a plan devised by senior priests behind the scenes.

It appears that what Nitchu experienced was quite serious. Pressured by assembly members, Nitchu expressed his intention to resign on November 22, 1925 and prepared a letter of resignation. Gladly accepting it, Assembly Chairperson Jimon Ogasawara[1] and other priests went to Tokyo that same day to submit Nitchu’s letter of resignation to the Ministry of Education, which was in charge of religious affairs for the nation. They completed the reporting procedure on November 24. As secretly agreed upon beforehand, the new high priest was to be Nichiko Hori.

The news that Nitchu was abruptly intending to resign reached the head of the Taiseki-ji lay group, who became furious that everything had been done so quickly without consulting the laity. The situation worsened to where lay society leaders vehemently protested to each of the assembly members on the following day, November 23.

Learning that the priests had gone to Tokyo to submit the notice of Nitchu’s resignation and Nichiko’s inheritance of the office, the lay leaders dispatched three representatives of their own to Tokyo to propose a counter opinion with the Ministry of Education. They begged the Ministry to nullify the assembly’s decision, insisting it was invalid. As an impoverished school at the time, priests could not afford to take the opinion of the laity for granted as they do today. If the laity pulled its support, especially from local temples, priests would be unable to support themselves and their families.

Hearing of the petition from the Taiseki-ji lay representatives, the religious bureau of the Ministry of Education summoned the three key figures of the assembly: General Administrator Koga Arimoto, who was chief priest of Myoko-ji in Shinagawa, Tokyo; Shudo Mizutani, who later became 61st High Priest Nichiryu; and Gyodo Matsunaga, who was chief priest of Denmyo-ji in Fukuoka.

The religious bureau was deeply dissatisfied by the coup carried out within Nichiren Shoshu and Mr. Shimomura, the bureau chief, severely admonished the three representative priests, asking, “You are responsible for leading and educating society, why did you take such an irrational action?” (December 3, 1925, issue of Shizuoka Minyu Shimbun). Additionally, the religious bureau ordered the representative priests to retrieve the documents given to Nitchu concerning the no-confidence vote and the recommendation for his resignation, and submit them to the Ministry.

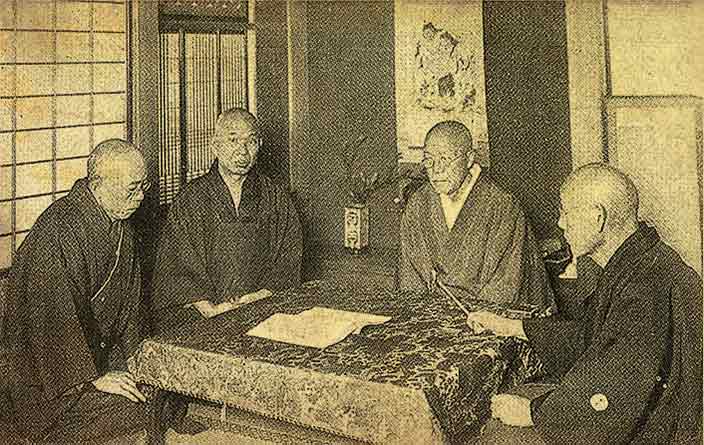

Eight lay representatives of the True Law Protection Group, which had formed as a result of the conflict, visited the Joren-bo lodging at Taiseki-ji to entreat Nichiko to change his mind and support Nitchu. It was January 29, 1926. Also attending this meeting was a leader of the local Taiseki-ji lay believers.

They actually met with Nichiko several times over two days. But the lay group’s maneuvering failed; Nichiko adamantly turned down their request.

On January 30, the group’s representatives arrived at Hashimoto Inn in Omiya Town (currently, Fujinomiya City) and discussed until late in the evening what they should do. It seemed certain that Nitchu would be defeated now that their efforts to persuade Nichiko had failed. They decided to take extraordinary action.

They went to the Omiya Police Station at 1 p.m. the next day, January 31, and met with Deputy Police Chief Hikita. They then returned to Tokyo on the 2 p.m. train. These True Law Protection Group asked Mr. Hikita to investigate the incidents to intimidate Nitchu. They pointed out that Nichiren Shoshu assembly’s no-confidence resolution against Nitchu the previous November was invalid. Later, Nitchu’s camp filed a lawsuit over this incident. The lawsuit prompted police to eventually investigate Nichiren Shoshu.)

Strife over the position of high priest continued. It was the worst situation that had ever developed at Taiseki-ji. But one day, it all came to a sudden, unexpected end.

The election for high priest was conducted as described in the local paper Shizuoka Minyu Shimbun dated February 12, 1926:

“Taiseki-ji, a major temple of Nichiren Shoshu located at Ueno Village in Fuji County, is now engaged in an ugly internal dispute. The school is divided in a confrontation between priesthood and laity over the election of its chief administrator. Nichiren Shoshu seems to have abandoned the school’s proud 700-year tradition, established during the days of Nichiren through the traditional transmission of the heritage of his Buddhism. Its shame is now being exposed to the public. Voting in this election ends on the 16th, with vote counting to start on the morning of the 17th. It is predicted that the Rev. Tsuchiya, the former chief administrator, who is supported by the laity, has no chance to win in this election. The Rev. Jirin Hori, the chief administrator’s current secretary, who is backed by the priesthood, will doubtless win. The Omiya Police Station, which is responsible for security of the area that includes Taiseki-ji, is planning to send more than ten plainclothes police to prevent possible disruption as major chaos is expected on vote-counting day.”

More than ten policemen were to be mobilized to protect the counting of the votes for the next high priest/chief administrator. The counting of votes started at 9:05 a.m. on February 17. The total number of votes possible was 87. Two people abstained. The total number of valid votes was 85 [points were assigned based on first, second and third place votes]. The outcome was:

Priest Jirin Hori: 82 points. (Elected)

Priest Shudo Mizutani: 51 points. (Elected)

Priest Koga Arimoto: 49 points. (Elected)

High Priest Nitchu: 3 points

The incumbent, Nitchu, received only three votes. Since Nitchu voted for himself, this means that only two other people voted for him. In other words, only two people were faithful to him. Though priests stress absolute obedience to the high priest, it seems they only follow him obediently when doing so is beneficial to them.

On March 6, Nitchu, his wife, his attendant priest, and two members of the True Law Protection Group gathered at Fuji Station, and then set off by car to Hashimoto Inn in Omiya Town. There, they joined the three other lay believers for a discussion. That evening, they were met by two lay members from Tokyo. The discussion continued until late in the evening.

The following morning, March 7, Nitchu and the others returned to Taiseki-ji in two cars. The purpose of their visit was to conduct a public transfer ceremony for Nichiko. The ceremony took place at 10 a.m. at the reception hall. A congratulatory reception followed at 2 p.m.

A private transfer ceremony was conducted between Nitchu and Nichiko for one hour, starting at noon on March 8. The following month, on April 14 and 15, an inheritance ceremony was conducted to officially introduce the new 58th high priest, Nichiko.

This brought to an abrupt end the drama over the position of high priest of Nichiren Shoshu. This resolution was a result of a reconciliation effort by Mr. Shimomura, the Ministry of Education religious bureau chief, who was instrumental in softening the attitude among Nitchu’s camp.

However, this was not the end of Ho’un Abe’s (Nichikai’s) schemes to become high priest, nor was Nichiko the last high priest to assume the position through an election.

As these events and many others throughout the history of the school prove, the supposition that only the high priest has access to the most sacred essence of Nichiren’s teachings is a complete fabrication. It is not only an insult to practitioners, but to the founder and his true intent that all people have equal access to what is holy and sacred in the universe and in their own hearts. The tragedy is that by proposing that the power of the Gohonzon is determined through a relationship with or obedience to the high priest, the power of temple parishioners’ prayer is ineffective. This is not Nichiren Buddhism.

[1] Jimon Ogasawara would later play a key role in the priesthood’s wartime behavior, proposing that Nichiren Shoshu adopt the doctrine that the Buddha is subordinate to the Shinto deity.